Optimists Prevail: My Grandfather’s Story

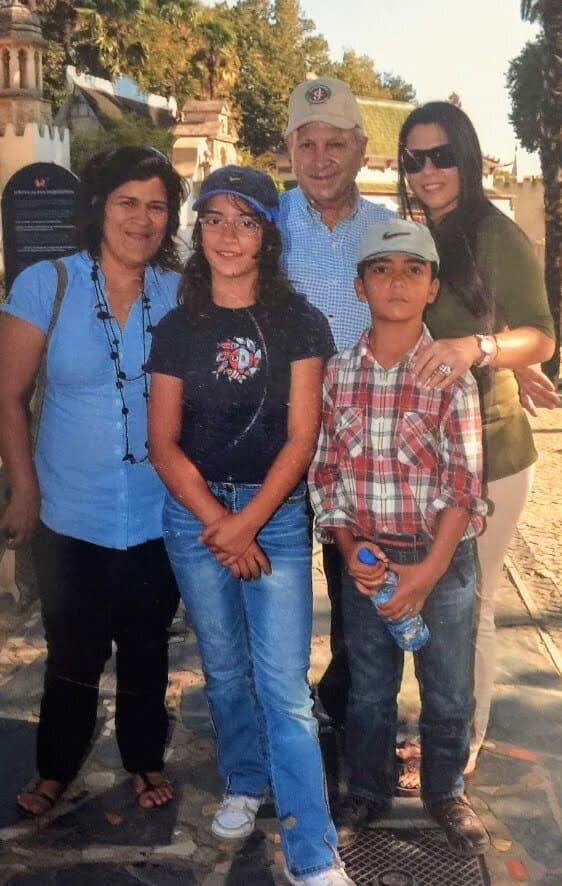

This essay is dedicated to my grandpa who recently passed away. He’s leaving an emotional emptiness for the many people who knew him but he’s also leaving a great legacy as a role model.

Juan Campolargo: The Man Who Beat The Odds

My grandpa emigrated from Portugal because of the war in the 1960s; his parents wanted him to have a better life instead of giving up more children to the war, so they sent him to this place called Venezuela where people seemed to live their lives to the fullest, everyone was prosperous, happy, nice, and healthy, and basically, everything that you needed and wanted could be easily found in Venezuela.

He boarded a ship to Venezuela at fourteen years old (keep this number in mind). After two weeks aboard this ship, he arrived at La Guaira (a city close to the capital of the country, Caracas) on June 27, 1957, a fourteen-year-old boy named Joao Campolargo Rosa arrived in Venezuela from Coimbra, Portugal, fleeing the seven wars that Portugal had opened, on the African fronts of Timor, Angola, Mozambique, Guinea, Goa, Dio, and Damau.

Joao—or Juan in Spanish—Campolargo (my grandpa) brought two heavy packages, a suitcase with clothes, and a briefcase full of chorizos and olive oil for luggage in that Atlantic crossing. Hidden among the victuals was an envelope with $400. While my grandpa was on the dock when he disembarked, a gigantic man, whose smile broke with a white glow all over his face, approached him and offered to carry the heavy bundles. My grandpa told me, “I innocently believed that this man was going to help me with my bag.”

Within a few minutes, the innocent teenager was alone, with no communication in the port of La Guaira, because the stevedore who had stolen everything he owned had vanished amid the hubbub of the noisy and hot harbor.

My grandpa understood nothing people said, and they did not understand him either in his tragic desperation—until in the chaos he heard words that he understood.

The person was Portuguese and had gone to the port for merchandise. The countryman knew Don Manuel Da Silva in Coimbra (my grandpa’s dad) and, understanding what happened, he took charge of the helpless fourteen-year-old boy.

He went to Chivacoa with the Portuguese man, whose business was carpentry. At his side, my grandpa learned as a bricklayer and carpenter in construction. He traveled throughout Venezuela and fell in love with the place until he settled in Yaritagua, where he made a stop with the 10,000 bolivars he had collected to transfer them to his father in Coimbra. It was a big buck, and with his restored pride, he was on his way to the bank when he was robbed and the money stolen. My grandpa says: “This was the saddest day of my life.”

After this nightmare, he began his journey in a country that would give him everything and nothing. He began working and doing any job he found to merely survive, one of which was being a construction worker, where he figured out a way to cut the wood pillars innovatively in the carpentry business. Everyone was impressed that this fourteen-year-old kid was able to do this job so well, and despite his age, he was quickly promoted to a manager position.

After this job, he had earned some money and was determined to start his own business. He realized that beer distribution was very profitable, so he took the challenge and bought a used Ford F-350 with which he would distribute beer to different states.

After a few months, he realized that there was huge potential in this industry, and he started buying more trucks and semi-trucks and hiring a lot of people. He was able to buy a big house, more distribution centers, cars, etc. At a very young age, he was already wildly succeeding.

Unfortunately, a big company named “Empresas Polar,” which at the time was trying to have a monopoly, bought the beer my grandpa distributed. He told me, “I could’ve easily become the wealthiest man in Venezuela if this hadn’t happened.” Following this, everything he had, including the trucks, distribution centers, etc were pretty much without purpose or use.

“Vacationing” Every Day

Something I found super interesting about my grandpa that I also find in many successful people, icons, and world-class performers is that they are never driven by money. People would ask him all the time, “Juan, why do you work so much? Don’t you have enough?”

My grandpa would smile and reply:

People think that I’m a machine that works only for money. But they don’t know that I don’t work. Every day I wake up very happy knowing that I’ll be going to my farms to see the animals, trees, and have conversations with everyone and anyone; things others do on vacation, I do every day. Although I earn a lot, that’s what I least care about.

- Juan Campolargo

People think that I’m a machine that works only for money. But they don’t know that I don’t work. Every day I wake up very happy knowing that I’ll be going to my farms to see the animals, trees, and have conversations with everyone and anyone; things others do on vacation, I do every day. Although I earn a lot, that’s what I least care about.”

My grandpa had another industry he was passionate about: livestock and farms. He found a guy who was supposedly selling about 100 acres of land, so he traded one of his semi-trucks for it. He was a man of his word and thought everyone else was the same, so he went to measure the land, and found not even half of what he paid for, so he went to talk to the seller, who was very rude and didn’t want to give the semi-truck back to my grandpa.

The next day, my grandpa went to the seller’s place and cut the truck into four pieces. This action was pretty wild; the seller must have learned his lesson! This piece of twenty acres ended up becoming one of the biggest farms in the state, with more than 2,500 acres.

Who would’ve thought that this Portuguese immigrant could achieve this type of success?

My grandpa had this goal in mind at a very early age; he used to go to a nearby farm that raised fighting bulls. He loved them, and over the years he developed an unbelievable passion for them. He told me that one day when he was ten, he used his cap to play with them, saying, “Olé!” He didn’t know that this was actually terrible to do, because you teach the bulls a different way to react when they go to the bullrings or “Plaza de Toros,” so he got beat up by a worker on the farm and since this day had told himself he would have the best bull-fighting livestock in the world, which he did.

He said to himself, “I will have so many of these bulls that I will lose count and would always be able to whenever I want to bullfight with them.” He never actually did a bullfight with them, but still.

After having many successes in Venezuela, my grandpa became financially stable enough to spend and invest large sums of money into this hobby and passion that he’s had since his early teens. He began this journey in 1978 by buying forty cows and one bull from a local livestock rancher until clearly becoming the best bull-fighting livestock in the country and, in 2014, in the world (you can see what I mean by following the Instagram page @ganaderiacampolargo, which I managed and created. It later served as a proven model of one of my businesses).

Dreams + Reality + Determination + Optimism = Success

Fifty years later, after everything that happened to him, Juan Campolargo is a renowned breeder of Yaracuy (the state where we lived). People who have worked with him, more than twenty-two men in his charge in various properties and trades, are heads of family who educate their children in schools that my grandpa has founded in towns of Yaracuy such as Jaime and La Yuca, counties and towns served by water and energy that he distributes for free to the community.

Currently, he’s a super active person, really optimistic, and healthy despite several bizarre incidents such as a bull that took out his intestines, falling from a four-story building, many car accidents, a jet accident where the pilot passed out and he somehow managed to land it safely, and so many more—yet he’s still safe and sound. He seems to have more lives than a cat. I wonder if I inherited some of his traits.

My grandpa has been an important part of my life, especially in the years before I moved to the United States. Besides my mom and younger sister, he was the person I used to spend the most time with. I learned so much from him: everything from business to life lessons to jokes and more.

One of the things I missed the most after leaving Venezuela was the wonderful experiences and interactions I used to have with him every weekend.

We used to live in a relatively small town with a population estimated at 200,000. My grandpa is one of the most well-known people in the entire state or even the country; he’s become widely well-known for several reasons, such as living there for a long time, businesses, farms, and the famous bullfights.

Whenever I could, I would be with my grandpa, working, doing the payroll on the weekends, buying and selling livestock, and taking care of the mighty fighting bulls. It was truly pleasant; I felt like I was in heaven just by being there.

Well, one of the farms is named The Paradise, so I guess I kind of was in paradise.

My Friday Nights

I remember Friday nights after getting back to school, I would rush to finish my homework because I knew I wouldn’t have time to do it. After doing my homework, I would quickly go to bed so I could get up early the next morning. At 5:30 a.m., I turned on the TV to watch my favorite agricultural show, which lasted about thirty minutes. At 6 a.m. I would take a shower, brush my teeth, eat something, and call my grandpa before 7 a.m. “Good morning, Grandpa, bendicion.” (It is a blessing, usually when you see your mom or dad or uncle, grandma, grandpa, pretty much anyone in the family who is older than you. When you greet them you would say, “Bendicion!”). “Are you in town today? I’m ready for you to pick me up,” and he would pick me up ten minutes later, as I lived less than half a mile from him.

Afterward, he would pick up a guy who would help him every day and sometimes bodyguards. At about 7:30 a.m., we would be on our way to one of the farms where he initially started, Las Peñas. We would stop to light a candle or put new flowers in the chapel that was built in the exact place where my father was assassinated.

Once we finally arrived, we would vaccinate or check the cattle, sell or buy the cattle, and do the payroll. We would be here until noon or so. We take the highway and come back to our city and pick one of my grandpa’s best friends, Antonio Torres. He is a person I deeply admire—I would talk to him for hours and learn so many things, about the universe, the speed of Earth’s rotation, science, history, and much more.

After we picked him up, we’d go to the other farm named, El Cilindro, or officially El Paraiso:

The Paradise. We would pretty much do the same thing we did at the first farm until about 4 p.m., when the routine of feeding the cattle is done at dusk, and in the family, where workers participated with the children as spectators. After a half-hour or more, we’d say goodbye to the bulls until the next day, when we’d return at the same time for the daily meeting with the bull caste.

It’d be about 5 p.m. by then, and some of my grandpa’s other friends would come, such as Alex and Kenny, who are originally from China. We would spend the rest of the evening playing really intense dominoes matches while eating some snacks.

At about 7 p.m., we’d say goodbye to everyone and go home, have dinner, and get ready for Sunday. Thus was a usual day I would spend working with my grandpa. I’d only go home to sleep, which sometimes I didn’t even do, and my mom would get really mad at me.

Relentless?

I think a lot about how my grandpa remained optimistic once he first got his suitcases stolen, and I even think about how I was able to remain optimistic after moving to the United States. I believe true optimism comes from true despair.

It blossoms in those moments of complete absence of hope when optimism becomes the only option. Optimism is the number one principle of living an extraordinary life. It’s crucial to control our minds because if we can’t, it does not matter how passionate we are, how compassionate or how optimistic we want to be. If we can’t control our minds, none of the other things you can be or learn really matter.

Imagine if you take two dogs and put them in two different areas. You shock the first dog and give him an option to escape. He tries to escape, he’s successful, and he gets away from the shocks. The second dog, however, you put it in a place where no matter what he does he cannot escape the shocks. He soon figures out that there’s nothing he can do, he gives up, and he just sits there and accepts the shocks.

Now you take these two dogs and put them in two new areas again, but this time they can both escape. The first dog, who had learned he was able to escape, will get out of there again. But the second dog will just lay there and accept the shocks, even though in this new environment he can just escape.

This phenomenon is known as “learned helplessness,” and I’m sure you know people like the helpless dog. The opposite of this condition is learned optimism. This concept of the dog was developed and studied by Martin Seligman. He was one of the first pioneers who started the movement of optimism and positivity in the early 2000s.

Common Traits & Patterns

The common trait I identified in both me and my grandpa was the narratives we used to make sense of the situations we experienced. When the thief stole my grandpa’s suitcases, he didn’t think for a single second that his new life was going to be a nightmare because of this, but rather saw it as the start of a new beginning.

Of course, he needed clothes and the little money he had to merely survive, and he was understandably mad about what just happened, but he found a way to become a realist optimist.

Elaine Fox, a psychologist at the University of Essex in England and author of a book on the science of optimism, Rainy Brain, Sunny Brain, also emphasizes that “positive thinking is not the main thing about optimism.” She stresses that “what really makes the difference is action.”

Do you really think that after my grandpa lost his only belongings in a new country where he knew neither the language nor a single person, positivity was going to help him? As Fox pointed out, action really makes the difference.

This idea goes back to what I earlier said about controlling yourself. The most important thing for becoming an optimist is to have control over your emotions and life so that when you experience a setback, you feel you can do something about it.

Optimism has nothing to do with feeling happy or a lazy belief that everything will be fine; it has to do with how we respond to adversity when times get tough. Optimists tend to keep going, even when the entire universe seems set against them. In the end, optimism is a skill of emotional intelligence, which translates to greater success in life.

A study performed with 300 college students studying at Ondokuz Mayıs University [1] attempted to find out whether or not the optimism level of university students could predict their levels of emotional intelligence. The study observed that the optimism levels of students are a meaningful predictor of their levels of emotional intelligence. In other words, the findings indicate that an increase in the optimism levels of students predicts the levels of emotional intelligence positively. Emotional intelligence deals with underlying human principles.

As our world and generation move forward, being optimistic can help you have more control over your mind (or narratives).

The Number 14

I lived in Venezuela for fourteen years of my life. Does that number sound familiar? That’s how old my grandfather was when he moved from Portugal. I guess, in some way, history repeats itself, and I was supposed to immigrate.

Believe it or not, I had this weird feeling when I turned fourteen that I would move. It did happen. I lived in this lovely place until 2016, and due to safety and political reasons we had to find another place where my mother and my younger sister and I could live safely without the fear of unjustly losing our lives.

My grandpa may be gone but he will always live in my memory as a guiding force. He has left a legacy of hard work, perseverance, vitality, optimism, and most importantly a desire to fully live.

Grandpa, I’ll try to live up to your legacy!

This was an edited excerpt from Generation Optimism: How To Create The Next Generation of Doers and Dreamers © 2019 Juan David Campolargo.

If you’re into interesting ideas (like the one you just read), join my Weekly Memos., and I’ll send you new essays right when they come out.